Global Health

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR), which is making a growing range of antibiotics ineffective, is an

increasingly critical problem. Driven largely by the improper use of antibiotics, AMR causes more than 1.2million deaths every year. As this resistance grows, it is eroding the power of a cornerstone of modern medicine. And if nothing is done, that figure is expected to reach 10 million deaths a year by 2050.

The problem is not new, and many in healthcare and government have been sounding the alarm for some time. Nevertheless, there has been little progress in producing new classes of antimicrobials. This is largely a market problem, rather than a scientific challenge. Antibiotics are ideally taken for short periods of time, which makes them less lucrative than drugs intended for extended use. Unable to make this work commercially, many pharmaceutical companies essentially stopped developing new antimicrobials years ago. In short, our approach to antimicrobial innovation is broken.

There are no simple solutions to AMR, but in the coming year, growing awareness of the problem may lead to action in several key areas.

Government will increase their focus on innovative incentives

Governments understand that they are key to finding lasting solutions to the broken AMR market. This is leading to actions such as a pilot program that pays for antibiotics based on their value to healthcare, rather than usage, and proposals to allow governments to compensate companies that create new antimicrobials by granting fast-approval status to their other, more lucrative drugs.

In late 2021, the G7 finance ministers released a statement on antimicrobial resistance, saying “We are committed to strengthen and intensify our action across the G7” and “recognizing that this is a multiyear and multistakeholder effort.” Such a statement from finance ministers—as opposed to health ministers—underscores the growing recognition of the need to address the economic side of the problem.

In addition, the U.S. Congress is considering the Pioneering Antimicrobial Subscriptions to End Upsurging Resistance (PASTEUR) Act, which has a good chance of becoming law in 2022. This legislation would create a program in which companies that develop new antimicrobials can offer their drugs on a subscription basis that provides revenue without requiring high levels of drug usage. Altogether, these efforts send a clear signal that governments are ramping up efforts to find new ways to incentivize antimicrobial development.

Countries are set to renew AMR efforts

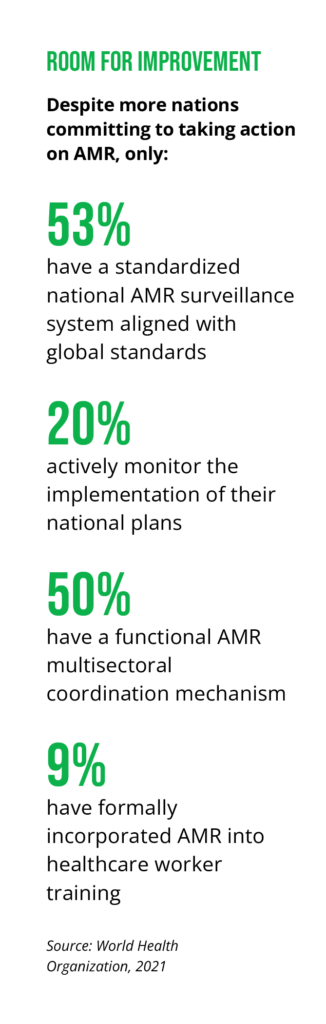

When the 2015 WHO Global Action Plan on Antimicrobial Resistance called for countries to develop national AMR action plans, many countries—including a significant number of lower- and middle-income nations—responded with plans that typically run for three to five years. Now, these plans are coming to an end, and those nations are poised to renew them. Thus, 2022 will see increased activity in countries’ efforts to assess the impact of their efforts, incorporate the lessons learned into new plans, and spell out how they will build response plans and surveillance capabilities and improve stewardship to rein in the unnecessary use of antibiotics.

Efforts to shape these new national plans in the coming year will be critical to the future of AMR, because they will drive the on-the-ground work that is key to translating ideas into action.

Private sector efforts will increase

The pharmaceutical industry has recently become more active in pursuing AMR solutions. For example, a few years ago the International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers & Associations (IFPMA) launched the Antimicrobial Resistance Industry Alliance (AMRIA), which includes more than 90 member companies. The group works on several fronts, such as promoting research into new drugs and stewardship to slow the emergence of AMR drugs.

Looking forward, the alliance and its members are likely to keep expanding their efforts. This could include improving the collection and sharing of AMR surveillance data, which a 2021 alliance report cited as an area for potential improvement. In addition, we are likely to see activity in the area of responsible manufacturing and reducing the “leakage” of antimicrobials into the environment. While members typically perform well on that front, the report says, there is now an opportunity to extend those gains into their supply chains.

Separately, the IFPMA formed an AMR Action Fund in 2020—essentially, a venture capital fund that aims to invest $1 billion in startups, with the goal of creating up to four new antimicrobial drugs by the end of the decade. To date, the fund has been working to organize and identify opportunities—and in the coming year, it is likely to start making investments to support clinical research, where there is often a funding gap. This type of action will be important, but as the fund itself notes, its main impact will be to buy time for governments to implement the innovative policies needed to address the fundamental market problems that drive AMR.